each work type Chromogenic print, edition of 5 + 1AP, 2014

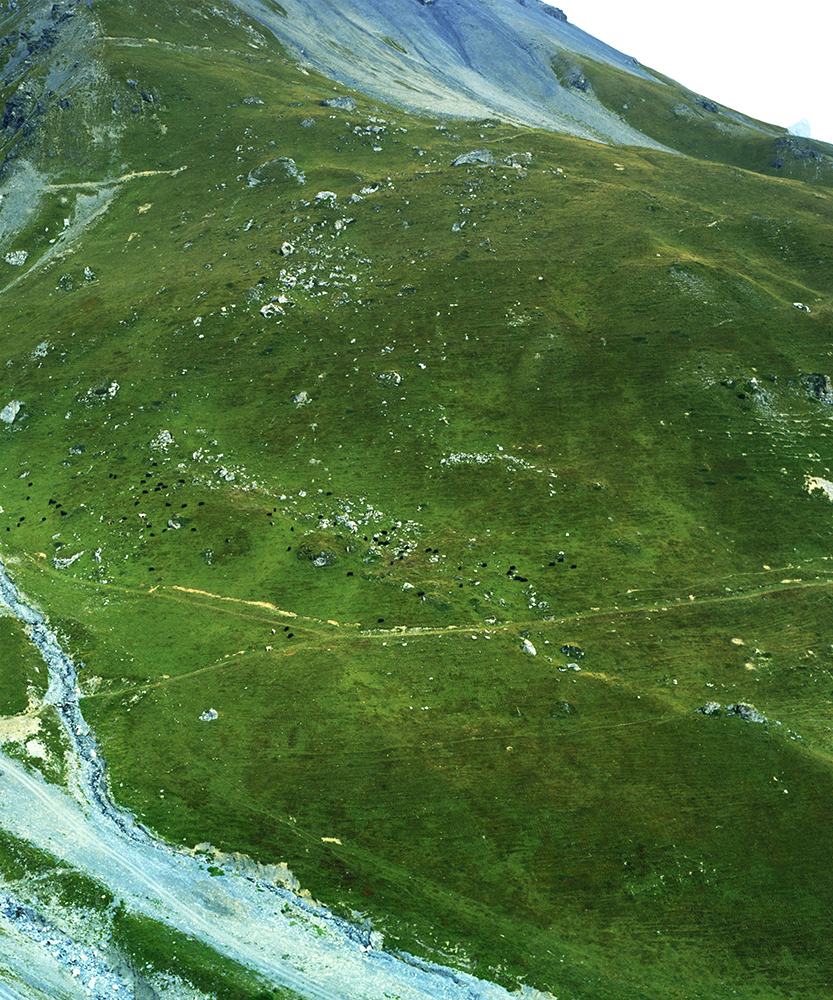

In the autumn of 2013, I was given the chance to work in Crans-Montana, a town located in the Swiss Canton of Valai. The

period was a month, from the last part of summer until the first snow began to fall.

From the valley town of Sierre, a funicular railway goes straight up to the station in Montana 1,500 meters above sea level,

the place where I would stay. Looking down, the Rhone River can be seen winding through the valley; from a point near the

station, gondolas carry people 3,000 meters up to the summit.

I had long been interested in the oral traditions of mountainous areas, and so I decided to make the lore of that region the

theme of my project. Even for Switzerland, the Valais Valley was quite isolated up until the 20th century, which was

fortunate since this meant it was a place particularly rich in folk stories and legends. But how many of them remained was a

concern. From what I could learn in Japan, it seems the oral traditions of the Alps have been disappearing in these modern

times, and the area of Crans-Montana, a luxurious mountain resort, is anything if not modern.

However, after my arrival in Switzerland, I found volumes of transcribed folklore in bookstores and storytelling taking place

in public venues. During my stay, I was even able to visit a museum dedicated to oral traditions.

I don't know to what degree oral traditions are being perpetuated, but it was a great experience to be able to meet people

attempting to record and convey these stories, and I felt this connected with the theme of my project, which was the

reconstruction of indefinite memories.

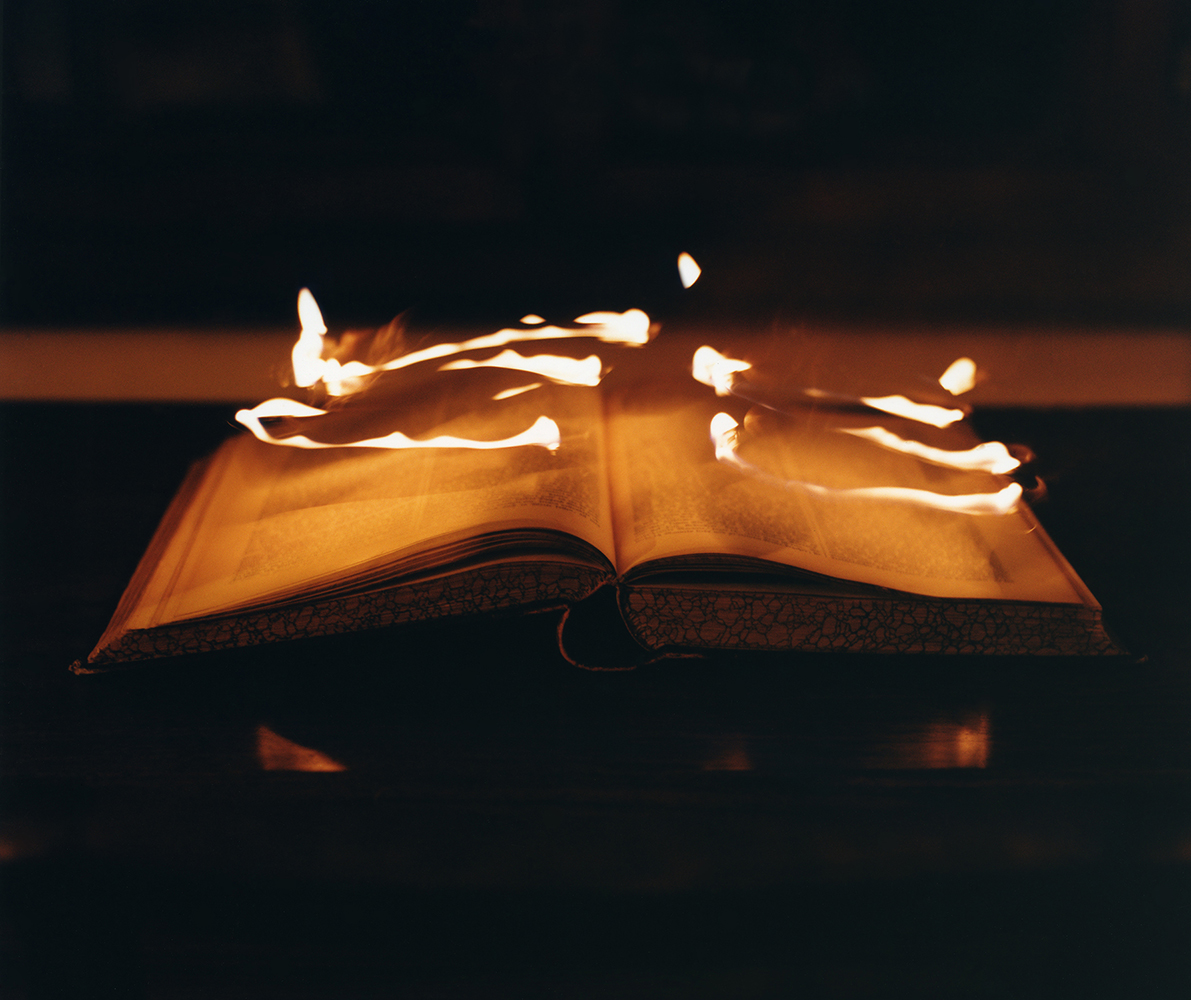

People living in harsh natural environments turned frightening, invisible phenomena that were beyond their understanding

into stories about the dead, devils, witches or fairies, which they then handed down through the generations. Many of such

stories traveled east and west along the Rhone River, changing a little each time they were told until variations of the same

stories could be heard in every part of the country.

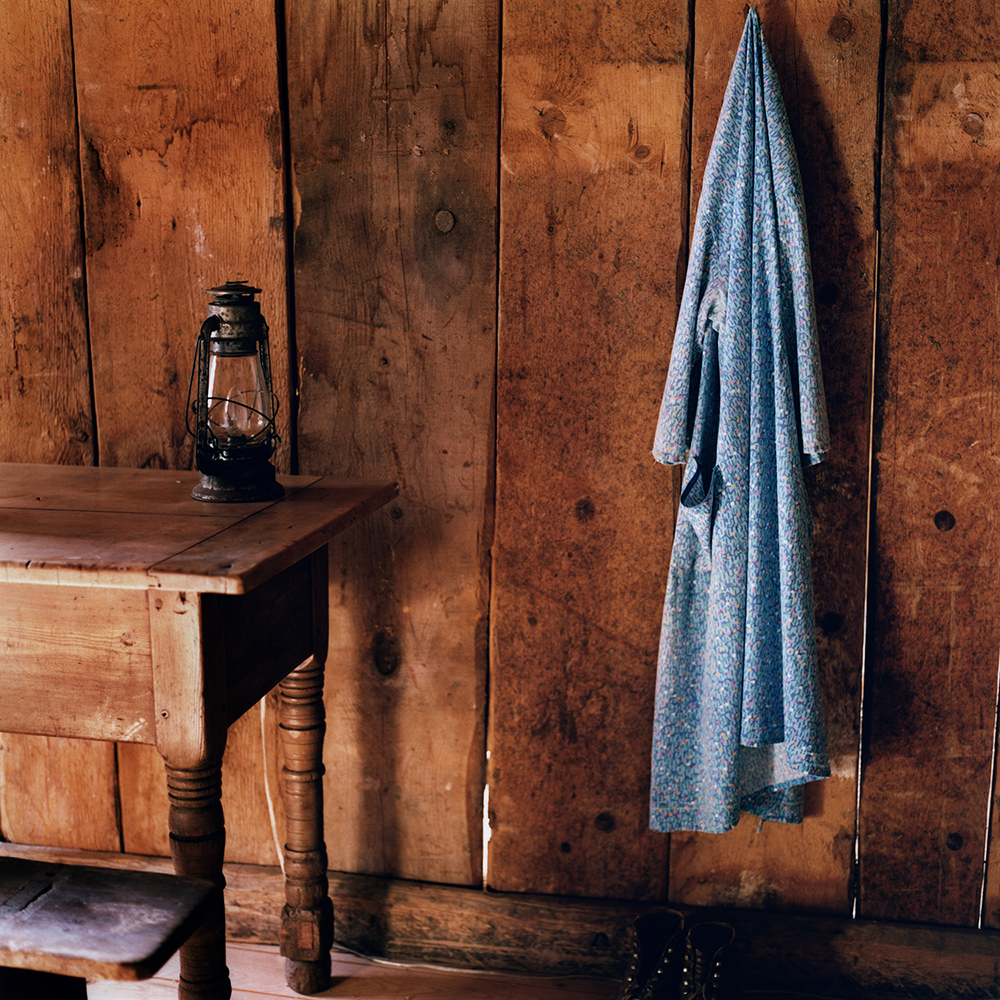

In the past, when summer arrived, cow-herding people in this region would migrate to chalets in the mountains that were

called "mayen." From there, they would go further up to meadows where they grazed their livestock and made cheese. In the

autumn, people, along with their livestock, descended down to the valley for the harvesting of grapes. Then came the long

winter nights shut in by the snow. It is within this traditional way of life that I believe oral traditions came into being, the

result of repeated migrations of people and stories going up and down the mountains.

For this project, I selected a number of extant folk tales and legends from the villages and mountains within Crans-Montana

and its environs and went to visit those places. Although some legends are connected with certain historical structures, in

most cases there are no geographical clues, which makes it impossible to identify specific places.

Giuded by stories of death, destruction and ressurrection, I went in search of nonexistent landscapes. In effect, I was

collecting memories that belonged to the land. What I saw there, it felt to me, was life itself, the life of the people.